He delivered the insult casually, as if it were a matter of little import. “I’m writing a story with someone else first,” he wrote in a brief e-mail message. “I think I can slot you in some time in 2011. Surely no later than 2012.”

He delivered the insult casually, as if it were a matter of little import. “I’m writing a story with someone else first,” he wrote in a brief e-mail message. “I think I can slot you in some time in 2011. Surely no later than 2012.”

People know me as a calm, placid man, slow to anger, uneager for confrontation, but this . . . this was the final straw.

Of course, I gave no sign of my rage at being so casually dismissed by the great Brian Keene. He who had collaborated with so many others in the past. Just about everyone on the planet, in fact, except me. My idea was a good one, a strong one, with real potential, unlike the drivel he had slapped together with those other hacks. I would have my vengeance upon this man, but in a manner in which no one would ever be the wiser. As Montresor pointed out, “A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser.”

We continued to exchange friendly e-mails. I kept up my end of our exchange with good humor and a sharp wit. The smilies I embedded in my messages would seem to him like I was in good spirits at our friendly banter. Little did he know that I was grinning at the thought of his demise.

I knew his weakness, though, and I would use it to my advantage. I put my expertise in search engine research to good use and soon had all the intelligence I needed to put my plan into effect.

It was late one evening at the convention. Keene had been regaling the others—most of them his former and current collaborators—with tales of his prowess as an auteur of some renown. He was even friendly to me and proclaimed that one day he and I, too, would work together on a piece, though his statement sounded patronizing and his smile ungenuine.

I returned the smile, equally as artificial, and drew him aside from his circle of fawning acolytes at the earliest convenience. “You’ll never guess what was just delivered to my room,” I said, circling my arm around his shoulder. “A keg of what passes for Knob Creek.”

“A keg? Surely not? Does such a thing even exist?”

“So the seller on eBay proclaimed. But I am unsure.”

“Impossible,” he said.

“I have my doubts, too. I thought I would ask Steve Shrewsbury to confirm it.”

“Shrews? No way.”

I shrugged. “The crowd in the bar said this his taste for bourbon is a match for yours.”

“Never. Knob Creek? I must see this at once,” he said. “Where is your room?”

“In the basement,” I said. “The better rooms were reserved for your collaborators.”

“We worked together once. Remember Looking Glass?

I kept my smile fixed and nodded. A round-robin novella hardly qualified as a collaboration.

“Lead the way,” he said, so I guided him to the elevator, which descended slowly into the bowels of the hotel. Keene staggered and lurched beside me as we traversed the long, dank corridor to the very end, toward a room adjacent to the furnace. At one point he seemed on the verge of retching.

“Come, let us return to the lobby,” I said. “You look ill. I’ll get Shrews to come in your place.”

“Enough,” he said. “A little too much drink will not kill me.”

“True,” I replied. “And if this is indeed a keg of barrel proof bourbon, it will cure what ails you.”

He withdrew a flask from an inner pocket and took a quick sip to gird him on the way. He did not offer to share it with me. Just as he had not offered seriously a collaboration.

Once more I took note of his unsteady bearing and encouraged him to turn back. He laughed and drained the flask. When he finished, he performed a crude gesture. I did not react. He peered at me. “Are you not of the brotherhood of Keene collaborators?”

“Ah, yes, of course.” I withdrew a copy of Looking Glass from my pocket. “Our collaboration.”

“Indeed,” he said and steadied himself upon his feet. “The keg. Let us proceed.”

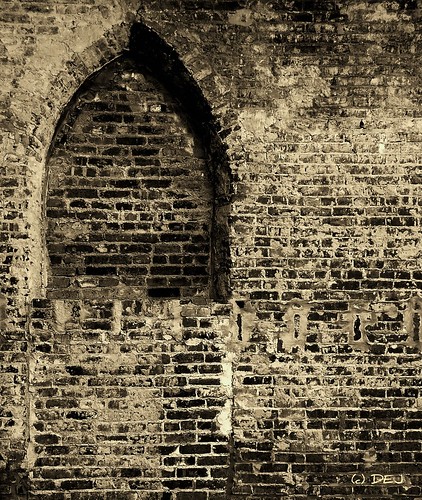

The basement walls were of bare brick and the floor of cement. The owners of the building had not even deigned to run a rude carpet along its length. As we approached the room, I readied the key.

The chamber was dark, dank and spare, without even a window to provide faint illumination. I switched on a lamp. Its weak bulb threw off feeble rays, barely strong enough to push aside the shadows. The room resembled a jail cell. On the floor: the oaken keg, charred and stamped with dates from the twentieth century. I had a tumbler at hand, a cheap plastic object that had once been wrapped in plastic and formerly occupied a place of ignominy, next to my bathroom sink. I held it beneath the tap and twisted.

Dark, reddish-amber fluid glistened in the feeble light. I held it up to my nose to savor the aroma, and made as if to drink.

“No, pass it here,” he said, greed burning in his eyes. Without even pausing to appreciate the nectar’s essence, he threw back the entire glass in a single draught and then commenced to cough. “Smooth,” he croaked once he regained the power of speech. Tears streamed from the corners of his eyes.

It took only a few moments for the tetrodotoxin to kick in. Extracted from the internal organs of numerous puffer fish, the potent neurotoxin had the desired effect. Though lethal in larger doses, a clever chemist such as myself knew the proper proportions to administer.

From that point onward, Brian Keene was conscious but completely under my control. His will became subjugated to mine. We would, at last, be true collaborators. I flipped open the cover of my laptop computer, launched Word, and typed in the title of the story that he and I had discussed but which he would never commit to writing. “Zombies on a Plane.” It was a brilliant idea.

I guided Keene to the chair. He followed without complaint or struggle. It was poetic justice—the zombie master was my zombie. “Write,” I said, and his hands groped for the keys and began to punch out words.

As he worked, I drew a second glass of poisoned bourbon from the keg. In fact, it was nothing more than Old Crow, the cheapest rotgut I could find. After a while I took my turn at the keyboard while Keene stared into space. He mumbled a few words at one point that sounded like “Knob Creek,” but I could not be sure.

For the next few hours, we went back and forth in that manner, the words falling into place on the screen like bricks in a wall. At the stroke of midnight I typed, “The End.”

“I must go now,” I told him. “Back to the bar. They will be wondering where I went.” I passed him the plastic glass and urged him to empty it, which he did without hesitation. This time he did not even choke or retch. He gasped one final breath before collapsing to the floor.

I pushed his slack body under the bed, barely more than a prison cot, and gathered my belongings. It was the work of another hour to return all of the boxes, crates and decrepit furnishings to the storage closet that I had claimed as my guest room. Many of the items had not seen the light of day in years, and I figured it would be many more years before anyone else excavated the room to discover what lay beneath.

After I finished, I locked the door and disposed of the key in the furnace. Then I returned to the lobby, carrying beneath my arm the laptop computer that bore the fruits of our labors. Brian Keene’s last collaboration.

THE END

Notes:

- With apologies to Edgar Allan Poe. Every time I read “The Cask of Amontillado,” I am awestruck by the story’s impact and power, as well as its brevity.

- “Brian Keene Must Die” day was inspired by a similar event last year in which Jack Haringa was dispatched all over the internet. We even published a book, the benefits from which went to benefit the Shirley Jackson award. While there probably won’t be a similar book this time around, if you feel like contributing a little to support the award, visit this link.