April 24, 2012

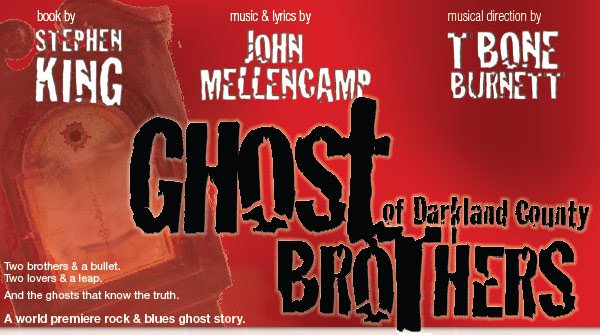

As I wrote last week, it took twelve years for Ghost Brothers of Darkland County to get from inception to execution. I attended the red carpet premiere on April 11. Here are my thoughts.

Before the show started, ghostly figures flitted across the stage, projected onto the walls. It was an eerie effect because I didn’t expect anything to be happening yet. I was talking to others in our group when I noticed motion out of the corner of my eye. Then we realized there were stationary figures at the edges of the stage. Was the old man sitting on a bus stop bench real or a mannequin? More of these figures materialized, part of the ensemble that would join the actors on stage from time to time.

Two thirds of the stage is taken up by the interior of a lakeside cabin. There’s a living room—which has a couch, a grandfather clock, a huge fireplace and a gun rack—and a small bedroom with a Shania Twain poster on the wall and bunk beds.

Beyond the cabin’s Spanish moss-covered roof is an old water tower. To the left is an open area used for exterior action and flashbacks. An old Pontiac convertible is pushed onto the stage here from time to time. In one wing is a lover’s leap. An elevated roadhouse set is located left of the cabin’s chimney. From this significant vantage point, a bartender and central character Joe McCandless contemplate the past. The four-piece band, composed of musicians who regularly play with Mellencamp, occupies a screened-in loft above the stage.

As the show starts, a figure emerges through a trap in the floor. Tattoos cover his arms and chest, and he looks like a satanic rockabilly singer. This is “The Shape,” a kissing cousin of Randall Flagg perhaps, played with sassy glee by blues singer/songwriter Jake La Botz. He sashays and saunters around the stage like he owns it. His opening piece, “That’s Me,” sets the tone. In it, he claims responsibility for every evil thought and malicious deed.

The Shape reappears frequently during the play, goading characters into making bad choices. He quickly becomes an audience favorite. For two generations he has been wreaking havoc on the McCandless family in the Mississippi town of Lake Belle Reve. Joe was ten when his older brothers died in 1967. Andy got easy As in school, whereas Jack struggled to make Bs. Their fierce rivalry worsened when a girl entered the picture. They argued and fought whenever Jenna wasn’t around, forgetting that young Joe was watching everything.

Jack unexpectedly wins the Hawkeye Shootin’ Competition. They drink too much that night and the love triangle comes to a head. What happens next becomes as romanticized in Lake Belle Reve as the stories of Cain and Abel or Romeo and Juliet. Only Joe knows the truth. His sons, Frank and Drake, appear to be heading down the same destructive path as his brothers. He needs to set the record straight so they can learn from the past.

Frank just sold his first novel for half a million dollars. He’s bound for New York with Anna—Drake’s ex-girlfriend, who bears a strong resemblance to Jenna. (The past harmonizes, right?) Drake blew his big chance when he screwed up during one of his band’s gigs with a talent scout in the audience. He’ll probably be stuck working at the local garage for the rest of his life.

Drake broke Frank’s arm during their most recent set-to, but Frank goaded him, so the two are equally culpable. Joe summons his sons and his wife, Monique, to the family cabin, the site of the long-ago tragedy. Anna comes with Frank, putting everyone on edge. Unlike Jenna, who was a pleasant, high-spirited girl who genuinely liked Jack and Andy, Anna isn’t nice at all. She’s probably with Frank only to torment Drake—she knows Frank is unlikely to take her to New York now that he’s found success. She spends a lot of the play slumped on the couch, seemingly uncertain why she’s there. Monique isn’t given much to do, either. She doesn’t know Joe’s secret but she encourages him and tries to keep her sons from bickering, but—even though she gets a couple of show-stopping songs—she is somewhat superfluous to the action.

The ghosts of Andy, Jack, Jenna, and Dan Coker (Christopher L. Morgan), the black cabin caretaker who unfairly received some of the blame for what happened in 1967, are interested in Joe’s story, too. They’re trapped in the cabin until the truth can set them free. Ten-year-old Joe (Royce McCann) chimes in occasionally, urging his older self to come clean.

The cast includes a Tony Award winner (Shuler Hensley as Joe), a Tony nominee (Emily Skinner as Monique) and a runner-up from the first season of American Idol (Justin Guarini as Drake), along with professional musicians La Botz and Kate Ferber (Jenna).

The songs range from R&B to C&W to rock and roll, mixed with ballads and Patsy Cline-esque torch songs. The vocal performances are all strong, though Ferber stands out in “Home Again,” “And Your Days Are Gone,” and “Away from this World,” and struts her stuff in a short dress and stockings in “Jukin’.” When the ghosts sing as a chorus, their harmonies are magical, and the full power of the ensemble is amazing. A program insert containing the final song listing indicates that King, Mellencamp and director Susan V. Booth tweaked the show right up to the last moment. A reprise was added to the second act, and the final song was renamed “The Truth is Here” from “The End is Here.”

The show’s staging, lighting and visual effects are all remarkable. When a character looks at a photograph, it is projected for the audience to see. As time ricochets back and forth, the years scroll backward and forward on the cabin’s roof. Other text cues occasionally appear on the walls. Panels in the floor allow characters and props to emerge on demand. The actors do double duty as props crew. Though those who use the lover’s leap are obviously jumping safely onto an air bag, the fact that they perform this ten-foot leap at all is impressive—and they have to do it several times. During the energetic dance routine—reminiscent of “Thriller”—that ends Act 1 (“Tear This Cabin Down”) the lights make the entire stage look like it’s on fire.

Like many Southern Gothic tales, Ghost Brothers hinges on a secret. When the truth is revealed, it may not seem like such a big deal, but it changes how the McCandless family is seen—and how it sees itself. The romantic legend loses its sheen. It is also a secret borne by a 10-year-old boy. As such, it shaped the fifty-year-old man he became. The first act dragged a little, with Joe dithering over how to tell his story—and how much of it to tell. The second act is much peppier, as the ghosts of the past and the present intermingle, tensions rise and the conflicts come to a head.

Signs outside the theatre warn of Stephen King levels of violence, profanity and adult situations. Certainly this isn’t family entertainment. There are numerous sexual references and sensual behavior (though no nudity), and jarring special effects associated with gunshots. Some of the violence is stylized, including the use of a transparent curtain that portrays flowing blood.

Viewers familiar with King’s other works will find themselves in familiar territory once the truth is revealed. King explored the need to make changes to get things right in the Dark Tower series and in an episode of Kingdom Hospital. The question is: who has to change and when do they have to do it? For a while, it looks like the show might end like a Shakespearean tragedy, but there is redemption.

There is no word yet whether Ghost Brothers of Darkland County will have a life beyond its run in Atlanta. King and Mellencamp fans who find themselves in Atlanta between now and May 13 shouldn’t pass up the chance to see this show if they can.